Exhibiting music highlights the challenge of presenting the intangible, through tangible and digital objects, with fragmented collections. In this post I explore these topics as experienced in various Museums of Music across the world while arguing that music can help close the gap between culture and heritage. In this post: Prague.

Czech Museum of Music – Prague (visited November 2025)

The museum “is located in the former Baroque church of St. Mary Magdalene at Lesser Side. The unusual symbiosis of the early Baroque church architecture with the classicist adjustment of usage and newly finished reconstruction of the Museum offers visitors a detail of an impressive combination of monumentality” (from museum website).

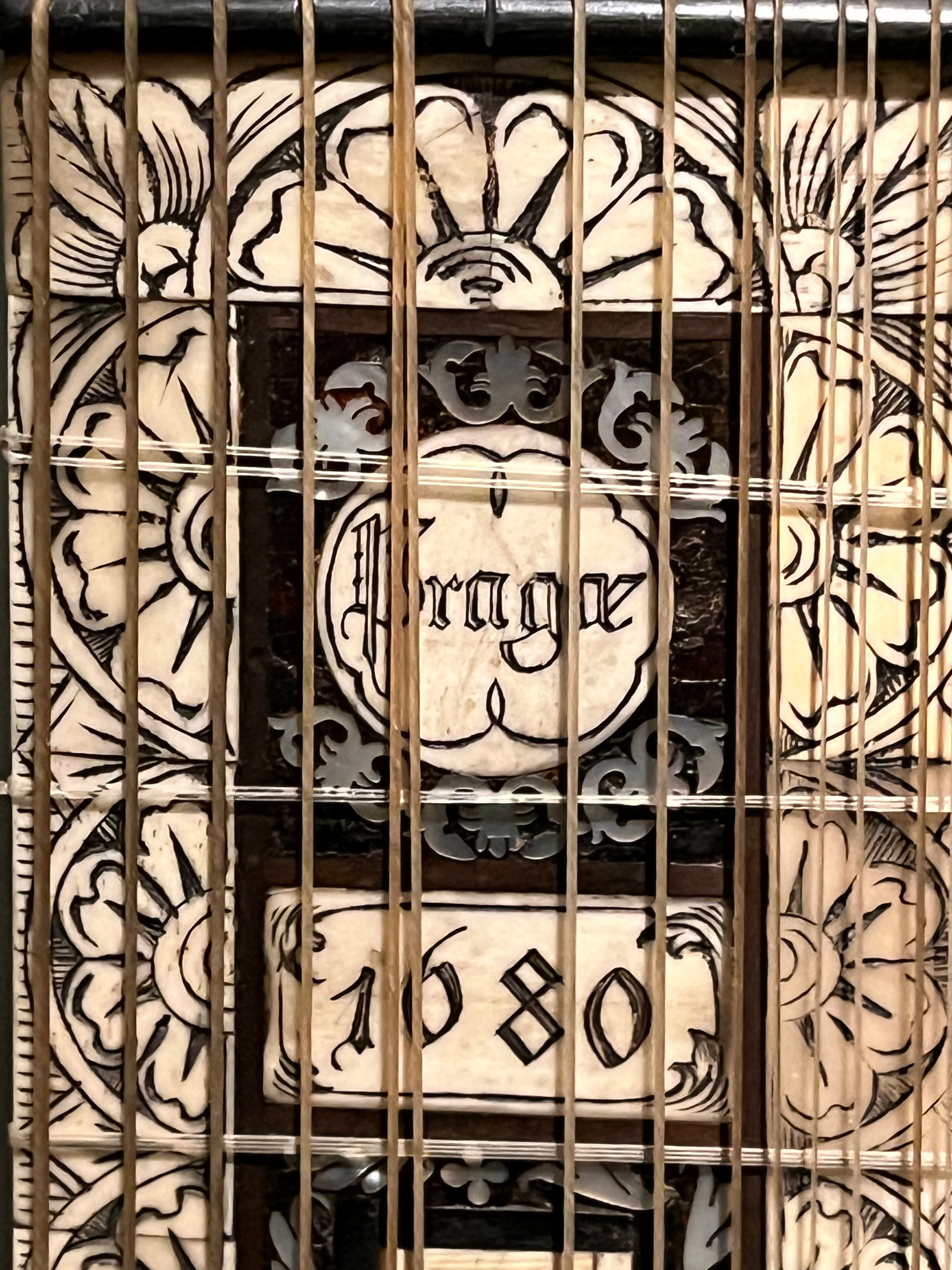

The first floor is devoted to exhibiting their collection divided in instrumental families. The collection includes 3,000 musical instruments (including those used in folk music), 38,000 iconography items, over 200,000 sheet music, over 100,000 audiovisual materials, and 100,000 related documents of musical history. Exceptional items include a piano by Franz Xaver Christoph that was played in 1787 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart during a visit to Prague, in his public concert at the Institute of Noblewomen in the ‘New Town’. The commemorative plaque from 1787, however, mistakenly remembers Mozart playing pieces from Don Giovanni, which could not have been possible as Mozart had just been given the commission for the work. He probably played variations on melodies from The Marriage of Figaro which was popular in Prague at the time.

Two other collections are displayed in their own memorial buildings: a collection of 9.000 items in the Antonín Dvořák collection, including autographs and his correspondence, and the Bedřich Smetana collection, including iconography, 3D objects, 29,000 photographic objects, 5,000 letters, music-related manuscripts, and recordings.

Display of the collection has a certain theatrical style.

The collection holds beautiful objects, here a selection of details from the strings family. While display follows the traditional format, there was care in ensuring proper light to showcase all their objects.

The museum also features some instruments used in folk music, such as the trumpet marine, the hurdy-gurdy, the fiddle, the bagpipe, the hackbrett, the zither, flutes, ocarinas, the gusla, the nail fiddle, and the fujara. All items in the collection are made by anonymous makers in the 18th and 19th centuries. Each one of them hold fascinating stories.

The trumpet marine is a bowed string instrument characterized by its elongated resonating chamber and single string, producing harmonics. Its unique bridge design creates a rattling sound when played vigorously, and it gained popularity in the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and early Baroque era in serious art music.

And an overview from the metals, displaying their unique collection of ‘Šediphones’ made by Josef Šediva – ‘two-headed’ brass instruments which were a popular component of Russian military bands in the early twentieth century.

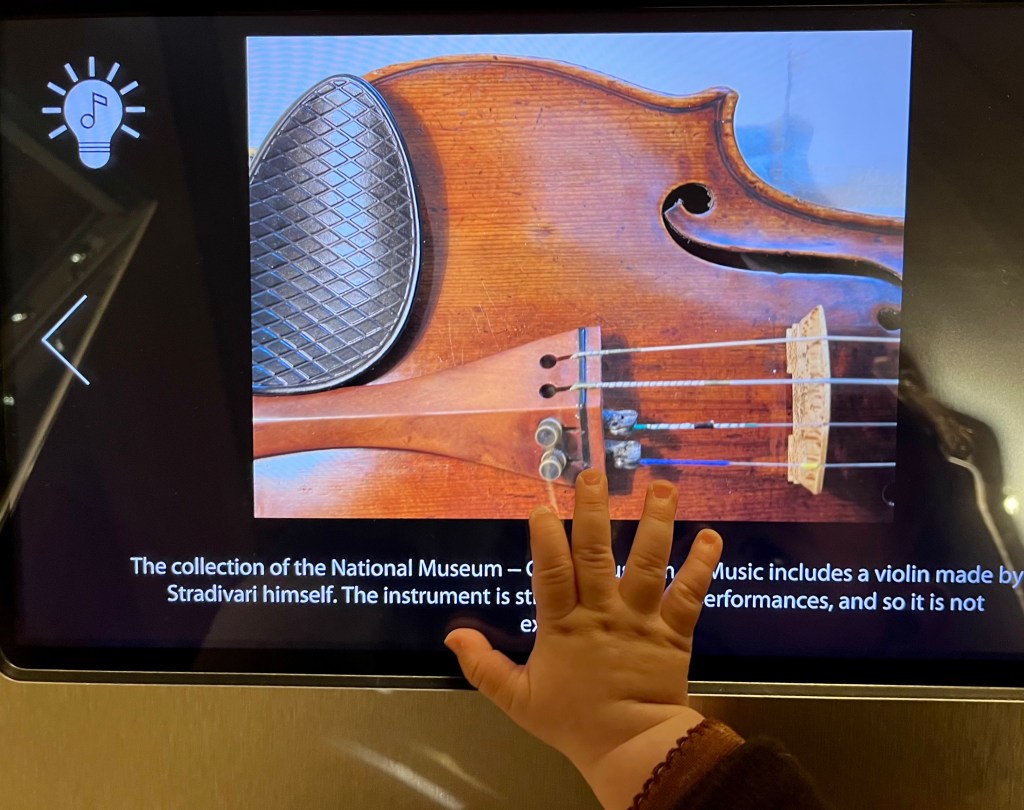

Besides the visual display, visitors could also listen to the audio tour (we did not know about this). Rooms also had digital displays with additional information about the collections.

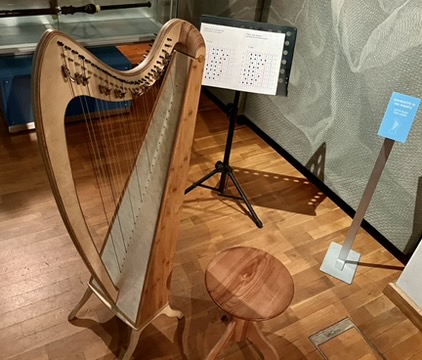

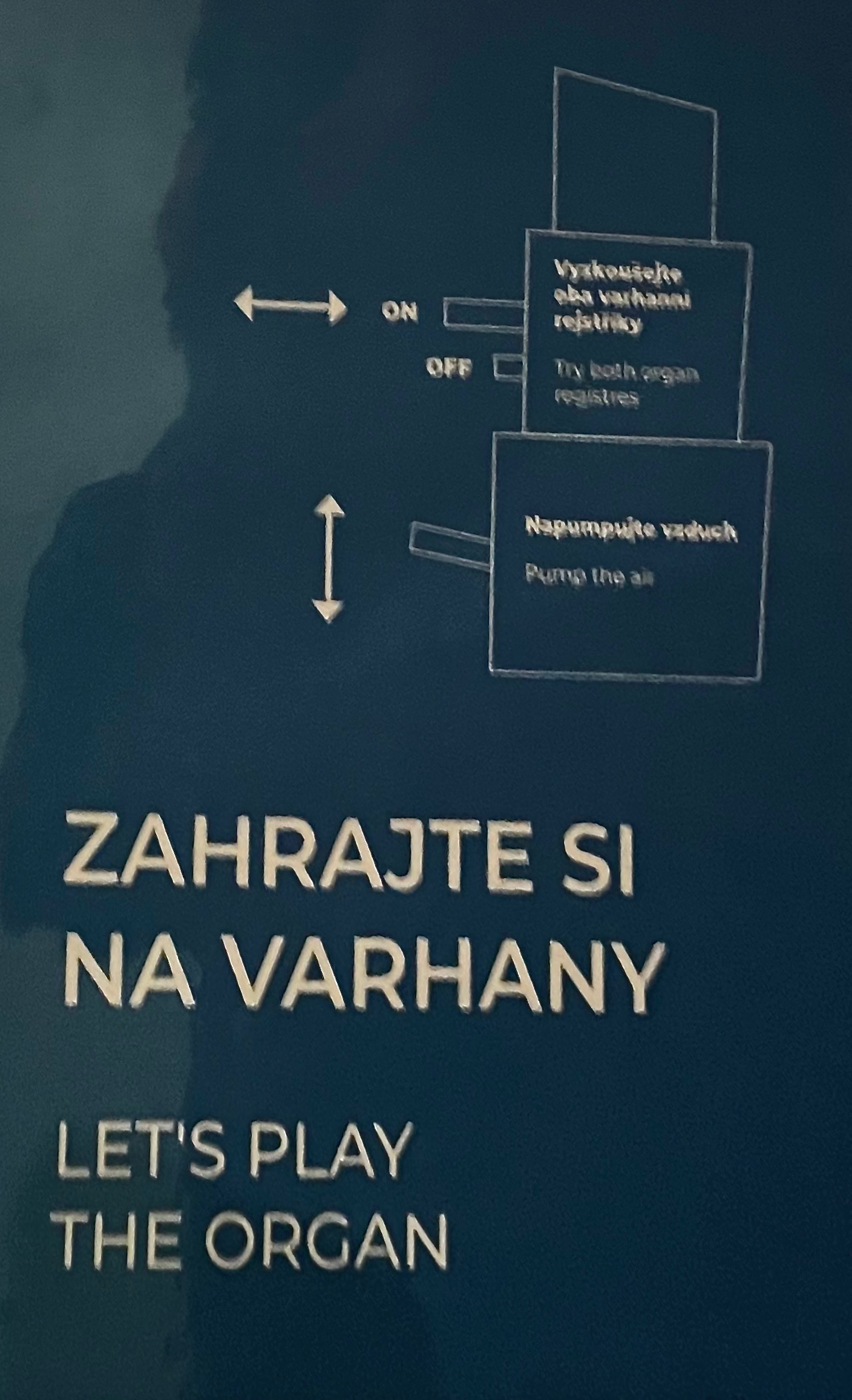

The highlight for us this time was the interactive elements, which my son loved. The museum provided lots of musical stimulation for playful souls with a musical staircase, as well as a harp, an organ, a marimba, and a percussion set available for playing. There is also a piano for use by visitors at the ground floor, which was well used by a group of young friends while we were there.

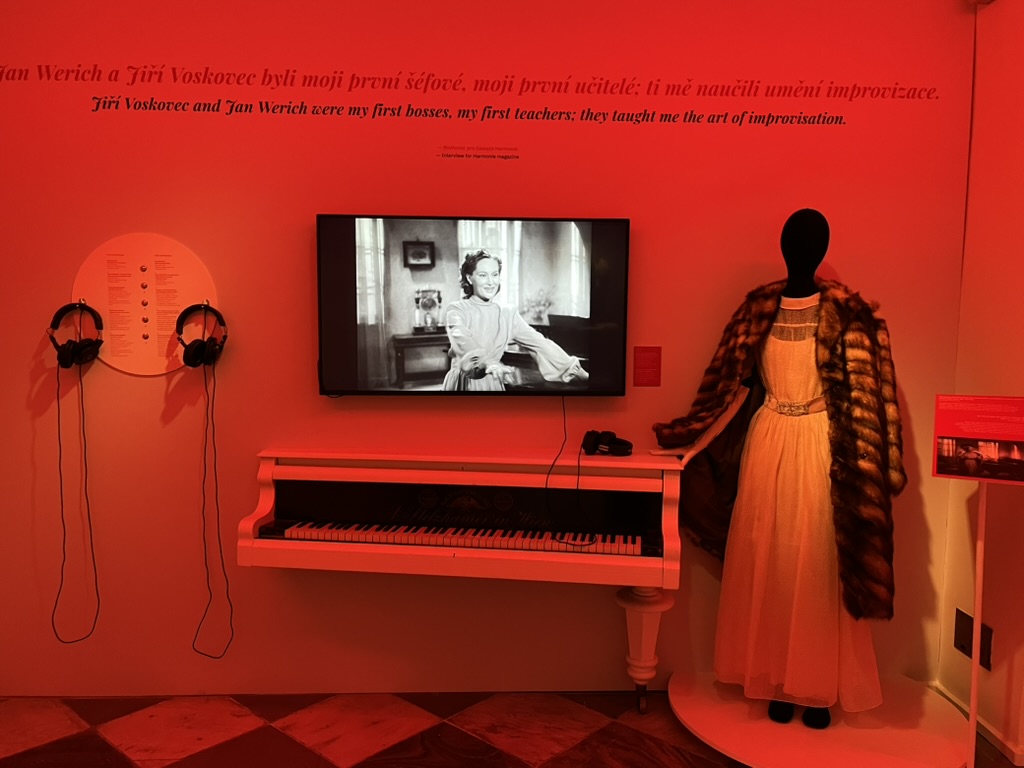

The ground floor displays the temporary exhibition. This time we saw an exhibition of mezzo-soprano and diva Soňa Červená on the occasion of what would have been her 100th birthday (Soňa Červená passed in 2023 at age 97). The exhibition features personal belongings, stage costumes by top designers, archival photographs, audio and video recordings, and documents from her personal and professional life. Her life traces her youth, emigration, successes on world stages, and experiments in drama, melodrama, and experimental theater after retiring from singing, which allowed her to be active until late in life. The extraordinary singer performed in 5,500 performances.

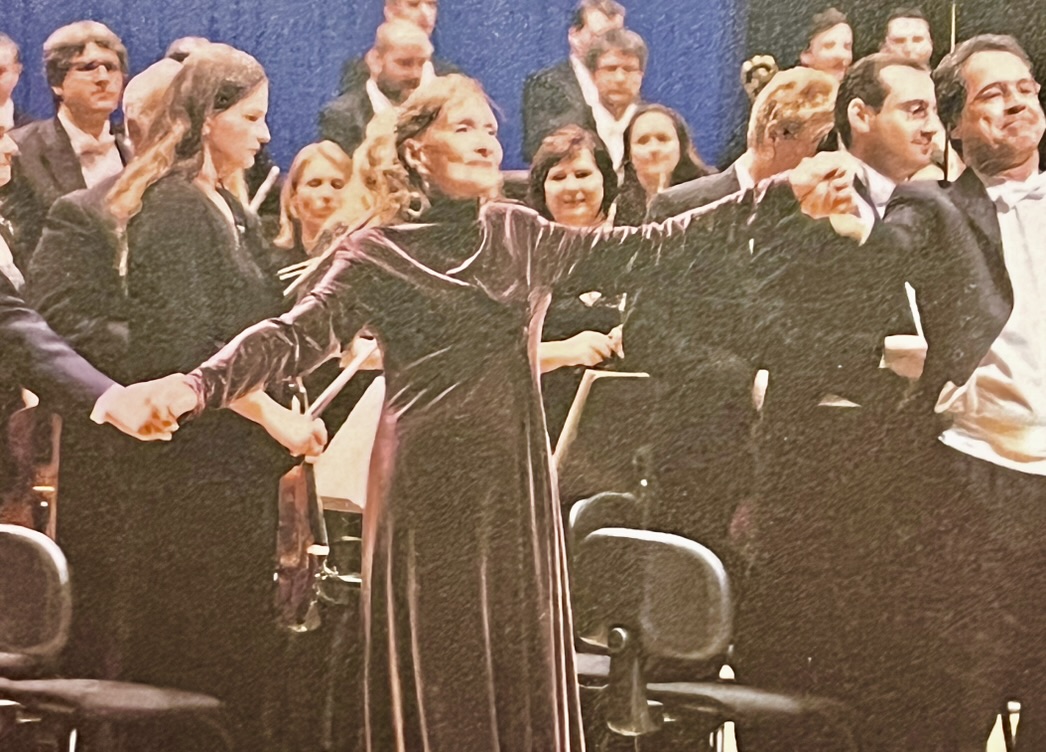

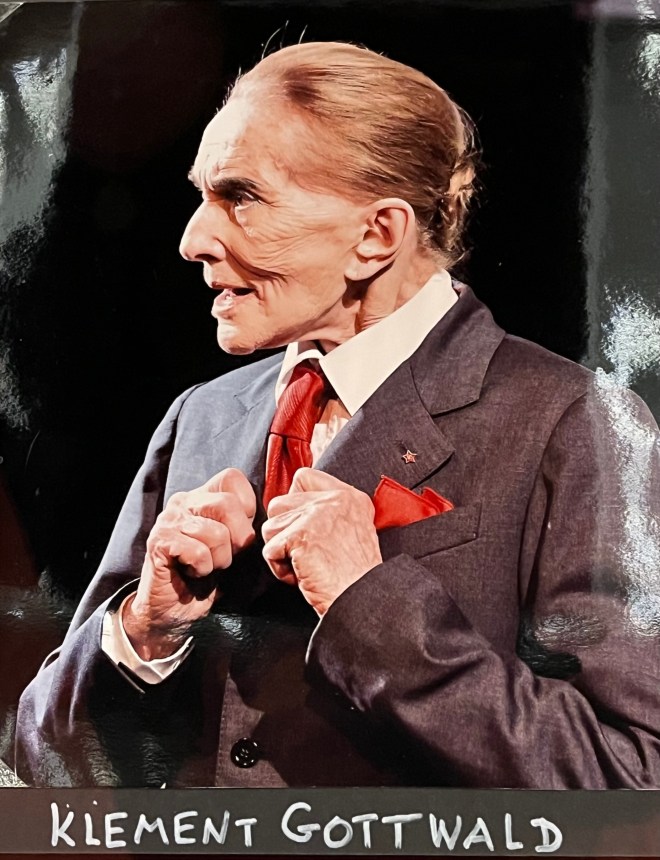

This portrait of Soňa Červená as Klement Gottwald shows her incredible endurance in sharing her artistic skill on stage. On 2022, at 97 years of age, she performs Jan Zástěra‘s ‘Breath of Eternity’ in Rome.

Given that we concentrated in the interactive elements and had little time to view the rest of the collection, we were happy with their Musical Instruments photographic atlas by Bohuslav Čížek from 2011 which describes their most important collection pieces with clear images.

The museum is children friendly, has a great toilet (important when travelling with babies), has a nice cafe, and though it does not have a breastfeeding room, we saw a mother finding her space near the cafe to feed her child. We will happily return to engage again with the interactive displays and the instruments.